Why does it matter? Aronofsky has said his new movie Noah is partially based on the comic book. It's not meant to be a plain rendering of the Bible story--which is probably a good decision for a moviemaker since Genesis 6-9 has no dialogue between human characters!

Is the movie biblical?

The movie will be critiqued for its faithfulness to the biblical story despite Aronofsky's clear disclaimer that the film is only inspired by the biblical flood. Since Aronofsky has to fill a couple hours with dialogue and wild guesses about Noah's personality and means of hearing from God, every biblical accuracy expert will have plenty to poke at.

But what elements must be in the movie to make it "biblical"?

However, the only "unbiblical" element is the lack of wives for two sons. The other elements should properly be called "extrabiblical." They aren't in the Bible story but are rather added for dramatic effect. Since they do not change the basic meaning of the flood story, they are simply extra narrative elements necessary to make a full-length film out of a Bible story you can read in 8 minutes. In fact, James McGrath has already presented a case for Aronofsky's trailer providing more historical realism than the planned Ark Encounter being built by Ken Ham's Answers in Genesis.

Personally I'm not that interested to pick on the narrative details Aronofsky adds to create a blockbuster film out of a short biblical story. But I am interested to know if he stays faithful to its central message. Of course, how do we figure out the central meaning of the flood story in the first place?

You might think readers can choose any theme or statement from Genesis 6-9 to make the central point. Such "reader response" theories of meaning have become popular in postmodernity. However, ancient Near Eastern oral storytelling techniques suggest there is one intended meaning to the story. And it's pretty cool to see how they do it.

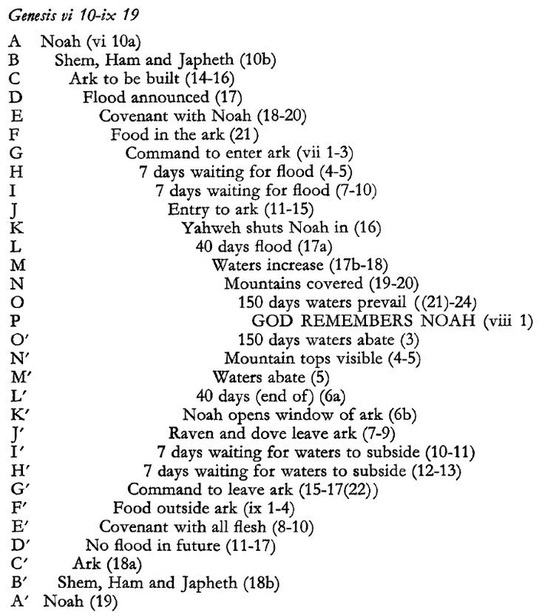

I have taught Hermeneutics (the art and science of correctly interpreting Scripture) in multiple settings for the past decade. One skill to master in biblical interpretation is understanding the significance of poetic structure--a feature found in more than one-third of Bible content. Genesis 6:10-9:19 provides a classic example of a poetic feature called chiasm. A chiasm helps people remember stories and preserve their meaning. Every part of a story or saying with a chiastic structure has a parallel idea presented in inverted order. The inverted parallelism of Genesis 6:10-9:19 is nicely summarized in the excerpt below from renowned Genesis scholar Gordon Wenham:

The first and last line tell us who the story is about. The only line without a parallel in the middle of the chiasm highlights the point of Noah's story. God remembers Noah (Genesis 8:1). Why is that a big deal? Because God made a covenant with Noah in Genesis 6:18-20. And that is the model for a parallel covenant God makes with humanity in Genesis 9:8-10. The point of the flood story is: God keeps his promises.

Isn't it great that literary analysis can clarify the meaning of the Bible? Bible interpretation isn't a subjective pursuit where what you like is right. Meaning is grounded in the literary, linguistic and contextual evidence!

God's faithfulness to his promises is not a surprising message. In fact, it's the dominant theme throughout all of Genesis. When God told Adam and Eve, "there will be trouble if you disobey my one prohibitive command," he wasn't lying. He stuck to that covenant stipulation. When Abraham thought his childless marriage to Sarah meant God was failing on his promise of many descendants, God showed up. When a famine could have meant the end of the family line with Jacob's sons, God turned the evil Joseph's brothers did to him into the preservation and proliferation of Abraham's descendants.

All these stories tell the audience: you can trust God's promises. He doesn't forget what he says even when it seems like he did. That's a message paramount to any faithful rendering of Noah's story. Does Aronofsky's Noah do it justice?

One Christian screenwriter Brian Godawa reviewed the Noah script and issued public comments about Aronofsky's "environmentalist" version of Noah. In his summary, the film portrays Noah as a "rural shaman, and vegan hippy-like gatherer of herbs" who "lives off the land." Noah's family "studies the world" to heal it from the degradation of human abuse "like a kind of environmentalist scientist."

Brian Godawa believes the movie will flop with Christian audiences because people are presented sinning against the earth not God. I'd suspect his prediction will come true among biblical literalists. But should Christians, Jews and Muslims whose faith is shaped by the flood story boycott the film for its environmentalist message?

There is a an early theme in Genesis about caring for the created order as God's representatives on earth. Genesis one commands humanity to care for the created world and everything in it. Genesis two recounts the beautiful garden God made for men and women "to cultivate and manage" (Genesis 2:15). These divinely ordained roles to care for the animals and cultivate the plants and trees do lend themselves toward an environmentally conscious and earth-friendly message. It is no creation ex nihilo on the part of Darren Aronofsky to build on this theme in his new Noah movie. There is a biblical basis for judging the righteousness of humanity on the way in which this caretaker role is executed.

However, the immediate context of the flood story in Genesis 6-9 makes the main problem clear. It is man's violence toward man not toward the earth.

Genesis 4 ends a list of Cain's descendants with Lamech bragging about murder. Genesis 6 picks up the same theme after Genesis 5 fast forwards the righteous line of Seth up to Noah. Genesis 6:13 specifically laments, "The land is filled with violence because of humanity." That's why God is going to destroy everything.

In Genesis 6-9, there is no mention of violating the command to rule over the animals as God's representative governors on earth (Genesis 1:28) or any accusation about humanity's general ingratitude or lack of stewardship of the plants and trees God gave them (Genesis 1:29). Rather the problem is the violence of men.

The end of the flood story reiterates the human violence problem. Genesis 9:6 lays down the law, "Whoever sheds man's blood, by man his blood shall be shed. For human beings are made in the image of God." People had been mistreating and murdering each other without proper respect for each person's representation of God on earth. That's the rampant problem on earth that moved God to judge. That is the corrupt environment in which Noah stood out as righteous, presumably for a more respectful approach to human life not the trees and animals.

If Aronofsky intended to represent the central message of Noah's flood story, he would make two statements rise out of all the creative elements he adds: (1) condemnation of the murderous rampages of ancient humanity (in this case the movie must be rated R to be biblical) and (2) commendation of the faithfulness of God to his promises, specifically to preserve Noah through the judgment. Based on the trailer and some screenshots like the one above, he has captured the "violence of men." However, public information about the script indicates the movie depicts Noah's righteousness through his environmentalism rather than his non-violence. So the biblical reason for the flood plays a secondary role.

Maybe the final cut will shift more toward Noah's righteous treatment of his fellow man, but I doubt it will happen. Aronofsky has publicly stated his intention to deliver a message about climate change through this biblical epic. He is intrigued by the idea of producing a "global warming warning call" of biblical proportions. Condemning humanity's violence toward one another just doesn't have the same contemporary appeal.

A Faithful and Unknown God

As for making God the hero who saves Noah and all the other creatures in the flood zone, we will have to wait and see. I don't have reason to believe God will play the dominant role in the film like he does in Genesis 6-9. So the faithfulness of God to his promises will likely not be the central message.

"No one should expect any kind of recognizable Christian or Jewish portrait of God in a biblically faithful flood story."

It was a mysterious era when men like Noah and Abram risked everything following visions and who knows what other types of revelation. So an inexact, confusing or even syncretistic portrayal of God would still be "biblical." I can't wait to see how Aronofsky handles this enigmatic process of interaction with an unknown God.

I also can't wait to write my next blog: The Positive, Biblical Message in Aronofsky's NOAH movie: The End of the World is just the Beginning...

RSS Feed

RSS Feed