| I have always felt uncomfortable with Jesus’ raw and cannabalistic claim: “He who eats My flesh and drinks My blood has eternal life” (John 6:54). It may be fitting for an outreach event to zombies, but I can’t stand even watching zombie shows—let alone becoming an immortal flesh-eating disciple. The reprehensible image probably explains why John 6:54 doesn’t show up on refrigerators and bumper stickers. But how should we handle its uncomfortable message? Is it just a metaphor for the Eucharist (i.e., eating bread and drinking wine at Communion) or am I missing something Jesus meant? To understand Jesus’ point, we have to hear his words like the first audience of John’s Gospel did. To listen with their ears, we must know who they were. |

Irenaeus, a 2nd Century bishop and theologian, tells us plainly where the author of John’s Gospel lived.

“John, the disciple of the Lord, who leaned on his breast, also published the Gospel while living at Ephesus in Asia” (Haer. 3.1.1; quoted in Eusebius Hist. Eccl. 5.8.4.).

If Irenaeus is correct, we know where John’s audience lived and can begin to explore their cultural context. However, some scholars have doubted that the same John who followed Jesus around the Galilee also wrote the Gospel of John. These scholars are not just cynics who want to undermine every plain truth in Scripture. Bible-believing scholars, and even Popes, have had good reason for asking who wrote John’s Gospel.

Eusebius, a 4th-Century church historian, makes reference to an Elder John (or John the presbyter). The reference to the “Elder John” comes from a second-century writer Papias. Papias spent time interviewing living sources about Jesus’ life and teaching. He wanted to differentiate between the real and the fictional stories about Jesus. Papias describes his trusted sources in a way that Eusebius thought referred to two different Johns living in Ephesus:

“If at any time someone came who had been acquainted with the Elders, I used to enquire about the discourses of the Elders-what Andrew or what Peter said (past tense), or what Thomas or James, or what John or Matthew, or any one of the disciples of the Lord; and what Aristion and the Elder John, the disciples of the Lord say (present tense). For I thought that the information derived from books would not be so profitable to me, as that derived from a living and abiding voice."

The key interpretive issue is whether the quote from Papias distinguishes between John the Apostle and John the Elder (or Presbyter). If they are different, then we should attribute 2nd and 3rd John to this “Elder.” Then the question of which one wrote the Gospel of John would be left open. However, the words of Papias make no such sharp distinction.

In the first line quoted above, Papias calls all the disciples “Elders.” It is his technical name for the “Apostles.” So when he refers to the Elder John, we can presume who he is talking about. It’s the same Apostle John.

The two references to John are simply the result of how long John lived. Papias was able to meet people who had both heard what John had said in the past but also continued to hear what John was saying about Jesus in his old age.

Identifying John the Apostle as John the Elder lines up with what all other church leaders from Asia Minor believed in the 2nd Century, like Irenaeus quoted above. The fact that Papias’s grammar made it hard for Eusebius to understand the connection can be explained by Eusebius‘s own critique of Papias‘s literary eloquence when he calls Papias "a man of exceedingly small intelligence, as one may infer from his own writings." Ouch.

Having settled the issue that John’s Gospel and the three letters of John were written by the Apostle, we can now examine who John’s audience was. John lived in Ephesus, a major city in the Roman province of Asia (western Turkey today). It is one of the seven cities to which John addresses his Apocalypse (i.e., the book of Revelation). That city was located in the heart of the Greco-Roman world. For centuries, the people there had been worshipping Greek gods. That religious habitat influenced which stories John selected for his Gospel.

You may have recognized that the Gospel of John is remarkably different than the three Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke). Apart from the common stories of feeding the 5,000 and Jesus’ death and resurrection, John chose unique stories about Jesus that related to his particular audience.

Clement of Alexandria (c. A.D. 155–220) tried to explain the differences in language and content between John and the other Gospels by explaining, “John, perceiving that the bodily facts had been made plain in the Gospels, being urged by his friends, and inspired by the Spirit, composed a spiritual gospel” (Eusebius Hist. Eccl. 6.14.7). Clement’s recognition of John’s unique angle on Jesus’ life and teaching is apropos, but claiming John wrote a “spiritual gospel” while the other three just gave the “bodily facts” is a culturally unaware conclusion. John did not get spiritual but rather contextual. He selected the moments in Jesus’ life where his teaching spoke most powerfully to an audience rooted in the religious worship of Greek gods like Aesclepius and Dionysius.

What would John’s audience imagine in their minds’ eyes when Jesus said: “He who eats My flesh and drinks My blood has eternal life” (John 6:54)?

Personally, I get sickened by the cannabalistic idea of eating human flesh. I watched a creepy movie about surviving a plane crash in the Andes mountains at too young an age. If you watched that movie, Alive, then you know the exact scene where they start eating human flesh to survive. But I don’t think John’s audience thought about pocket knives digging into a dead passenger’s back side. They had a much more graphic ritual of eating and drinking gods in their culture.

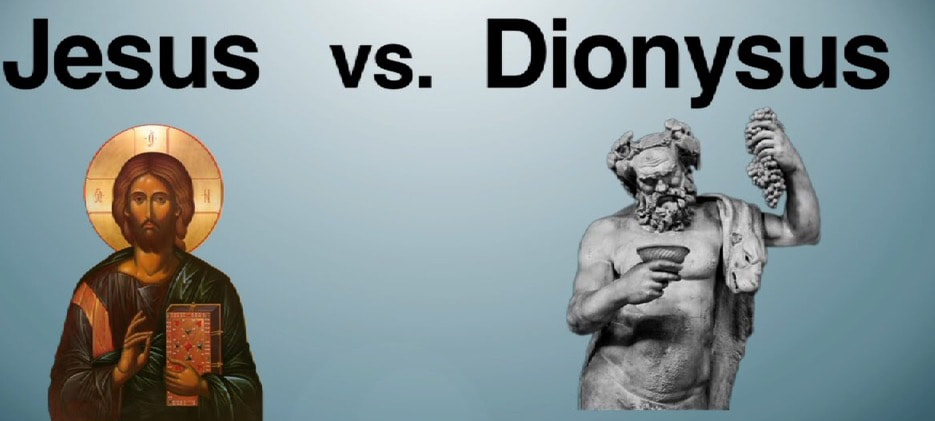

The same Clement of Alexandria who recognized the “spiritual” character of John’s Gospel knew of pagan spiritual pathways that competed against Christ. Some of them were grotesque. One pathway included amophagy (pronounce it however you want). Amophagy is eating raw flesh. The raw flesh embodied a god. As Clement witnessed, “In honor of a mad Dionysus, they celebrate a divine madness by the eating of raw flesh.”

Worshippers of Dionysius didn’t just go mad eating raw flesh; they literally went mad getting drunk on wine. Early in the second century Achilles Tatius described how Dionysius would reveal his presence at parties by turning water into wine. Confounded guests would ask: “Whence my friend, do you have this purple water? Whence have you found such sweet blood?” (Achilles Tatius, 2.2.1). This “water of summer, blood of the grape cluster” was an annual sign that Dionysius was returning from the underworld to bring new life to earth. So people would indulge in great bouts of drunkenness to celebrate this god of wine bringing new life to the earth.

The drunken parties of Dionysian worshipers became so integrated into Greek life that Plato himself gave his approval. Despite his typical critique of intoxication, Plato made an exception "on the occasions of festivals of the god of wine."

Greek philosophers embraced the drunkenness because of its spiritual power. Euripides said that a participant in the Dionysian mysteries "is pure in life, and while revelling on the mountains, has the Bacchic communion in his soul." Bacchus was another name for Dionysus. Euripides is here claiming that drunken participation in mysterious rituals put people in direct contact with the divine life. The blood and body, the wine and raw flesh, created communion with god. Yeah, I know; I’m glad I didn’t live back then either!

The Dionysian worship rituals of “amophagy” and wine-drinking bled into the sacred rites of other Greco-Roman religions. The Orphic cult built by Orpheus borrowed Dionysian ritual initiations. Diodorus states it plainly, "Orpheus being a man highly gifted by nature and highly trained above all others, made many modifications in the orgiastic rites; hence they call Orphic those rites that took their rise from Dionysus."

Entry into the Orphic cult required the amophagy, or feast of raw flesh. The Orphic "red and bleeding feast" was a communion service where god and man became one. Eating the flesh of the bull connected a man's soul to the spiritual life of the god Zagreus. That communion began a long regenerative process. Initiates believed their divine ingestion would ultimately give them immortality after death. That’s a pretty significant outcome tied to eating uncooked bull meat!

Because of how common it was to eat and drink your way into communion with gods, Firmicus Maternus had to condemn participation in these pagan rites in De errore profanarum religionum.

“It is another food that gives salvation and life. Seek the bread of Christ and the cup of Christ!"

As Heinrichs summarized:

“After the rise of Christianity, Dionysus had emerged as the leading pagan antagonist of Christ. Dionysus and Christ had much in common. Both had conquered death, both obscured the distinction between blood and wine, and both promised their followers life after death.” (Henrichs 1984, 212-13)

We can’t understand why John links eating flesh and drinking wine to Jesus’ offer of eternal life until we get into the theological claims of the Greco-Roman world. When we see the competing offers from alternate gods, we get it.

Jesus needed to make counter-claims. He needed to call out fake gods. He needed to make his promises in the metaphors that captured people’s imagination. So he became all things to all people so that he might save some—even if his Greco-Roman religious imagery is a little creepy in a post-mythological milieu that finds divine cannibalism a bit off-putting.

| Eating and Drinking in the Semele-Attis Cult The esotoric liturgy of the Attis cult originating from Asia Minor practiced a similar initiation for worshippers wanting to become one with God. Remember John’s audience in Ephesus lived in Asia Minor. Clement of Alexandria compared the initiate’s eating and drinking to consummating a marriage: I have eaten out of the drum: I have drunk out of the cymbal: I have carried the Kernos: I have entered the bridal chamber. Firmicus Maternus confirms the pattern and purpose of eating and drinking to create a mystic communion with Attis when he recites a similar statement of the initiates: I have eaten from the drum: I have drunk out of the cymbal: I have become a mystic votary of Attis. The eating and drinking to achieve divine communion that guarantees eternal life with the gods mirrored the Eluesian mysteries where initiates drank a mixed barley potion and ate sacred food from the chest. The list could go on. The point is this: When John writes the words, “He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood will have eternal life,” he is alluding to a pattern of worship dating back more than 1,000 years in Greek culture. The words are not unusual or opaque. They were pointed and powerful. They were part of everyday experience for people who wanted to connect with God. |

In John’s Gospel, Jesus speaks in remarkably different metaphors and syntax than the Synoptic Gospels. Why? So his words would dramatically connect with a primarily Hellenistic Jewish audience engrossed in Greco-Roman culture and beliefs. For Jesus to demonstrate his supremacy to that audience, he had to outdo the gods competing for their attention at New Year’s festivals (where the god Dionysus took center stage) and at local “hospitals” (or healing sanctuaries built around the god Aesclepius). He had to deliver his message in language that people used to express their desire for God.

That’s why he uses grotesque metaphors that some first-century folks thought were the magical path to the life of the gods. Jesus wanted to redirect people’s worship. He offered immortality to those who eat and drink him so they would stop participating in the eating and drinking rituals that unite people to Dionysus. Again and again and again (John 2, John 6, and John 15) Jesus asserts his superiority over Dionysus in John’s Gospel to draw devotion away from one of the most popular and influential Greco-Roman deities. He is not teaching general principles about the Eucharist in John 6; he is attacking a competing promise of eternal life.

Not everyone could handle it. Jews in the Synagogue started arguing, “How can this man give us his flesh to eat?” (John 6:52). His own disciples said, “This is a difficult statement; who can listen to it?” (John 6:60). After he finished explaining he was the “bread of life” (to speak to his Jewish audience influenced by Torah) and they should eat him (or look for spiritual life in him not the Greco-Roman mysteries), people freaked out. John 6:66 reports, “As a result of this many of his disciples left and were not walking with him anymore.” Sometimes powerful metaphors don’t land. Or maybe they promise more than people can really believe.

What Would Jesus Attack Today

Admittedly, Jesus’ words in John 6:54 do not have the immediate relevance to us that they did to Hellenistic Jews, but we should explore the competing claims in our contemporary culture that Jesus would challenge today.

We don’t live in a spiritistic society so our competing promises of life and safety come from materialistic concoctions. Pharmaceutical companies offer healing to every problem while soaking up profits from off-label use of deadly drugs. Fast food and industrial farming promise low-cost, quick eats while replacing nutrients with new chemicals that deconstruct God’s design. Do not embrace either chemical solution to our problems with the hope that only Jesus can handle.

We must make sure not to give ourselves wholly to any other power promising life, except Jesus himself. The rituals keep changing and the wording around what we seek morphs, but it’s just the latest Dionysus in polished postmodern marketing campaigns. Technological titans demand our pursuit of a better life in their latest versions, but be wary of where you put your hope. We must critically dissect any cultural expectation that life as God intended can be had outside of a connection to Jesus. Jesus is what nothing else can be. Feast and drink to that.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed