“You are Peter,

and on this rock I will build my church,

and the gates of Hades will not be able to stop it”

- Matthew 16:18

But what are the “Gates of Hades”? Is it Hell or an evil city or a band of demons roaming the earth? And what rock is Jesus building on? To answer those questions, we must look around the region where Jesus said these words. There is a long history of divine assemblies on tall mountains and kings who return from the dead.

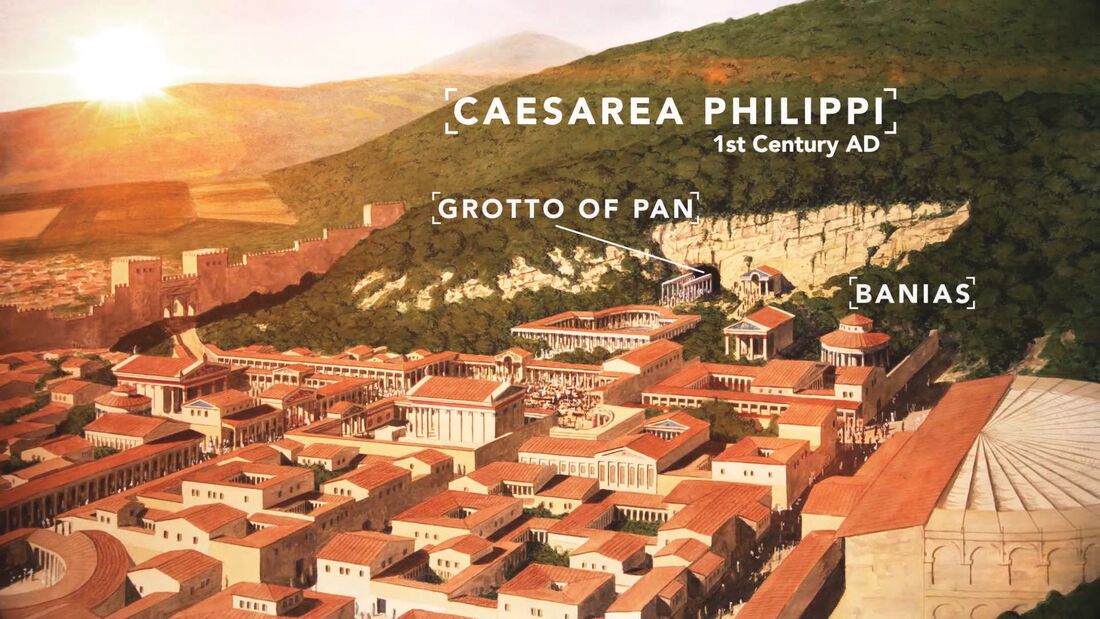

Jesus’ revelation of his identity in Matthew 16:13-17:21 takes place in Caesarea-Philippi. The city of Caesarea-Philippi sits at the northern border of ancient Israel (in an area called the Golan Heights today). The region is mountainous, with the highest peak reaching 9,232 feet. The mountains above Caesarea-Philippi are so high that a ski resort exists there today! But Jesus did not take his disciples to this region to carve through some fresh powdery snow. So why did he?

The inhabitants in Jesus’ time called the city at the base of the mountain, Panius. Panius honored the Greek god Pan who had been worshiped there for centuries before it got its name changed to Caesarea-Philippi. Josephus described Panius as the place where there is:

“a top of a mountain that is raised to an immense height, and at its side, beneath, or at its bottom, a dark cave opens itself; within which there is a horrible precipice, that descends abruptly to an immeasurable depth: it contains a huge amount of water, which never goes anywhere; and when anybody lets down anything to measure how far down the earth is beneath the water, no length of cord is sufficient to reach it.” The unique geological features at the foot of Mount Hermon earned it a special reputation. People believed the deep cavity in the cave led down to the underworld. For centuries prior to Jesus’ visit, people thought spirits of the dead could enter and exit the underworld through the watery abyss in the cave. This suspicion gave birth to some unusual beliefs about the inhabitants and their kings in the area. |

Great Kings Who Returned from the Dead

Numbers 13:30-33 says the ancestors of the Anakim and the Rephaim who lived in Bashan were the Nephilim. Who are they? The Nephilim were the offspring of “sons of god” and women according to Genesis 6:1-4. Although the “sons of god” in Genesis were likely powerful men who forced themselves on women, Jews in the Second Temple period (~2nd Century BC) came to believe they were spiritual beings that mated with humans. Their offspring were gigantic “evil spirits” walking the earth (see 1 Enoch 15:1–12). Yikes! Now that’s a story you wouldn’t forget.

But let’s stick to our story about Jesus by asking this question: How are gigantic Nephilim whose offspring became powerful kings associated with evil spirits relevant to Jesus’ words in Caesarea-Philippi? The answer begins with their shared geography. Enoch 6:6 situates this entire otherworldly episode about “sons of God” mating with women at Mount Hermon. Mount Hermon was the towering mountain range in the land of Bashan that rose above Caesarea-Philippi.

Since these events took place right where Jesus had stood with his disciples, we need to know more of the story. According to ancient Canaanite lore, the Rephaim (whom the Israelites connected to the Nephilim) were re-embodied spirits of dead kings. They had returned from the place of the dead to wreak havoc on earth.

The Hebrew prophets speak of the Rephaim similarly. The prophet Isaiah used the term Rephaim to speak of the spirits of dead kings who resided in Sheol—the Hebrew word for Hades (see Isaiah 14:9; 26:14). Although the Ugaritic and Hebrew writings have their differences, both tell a story of semi-divine, powerful men with evil intentions who originated from the region around Mount Hermon (NOTE: Ancient Canaanites believed all people who died and came back to life were in some sense considered “divine”).

Although these semi-divine legendary kings were powerful, they could be defeated in battle. Israel actually defeated the Kings Sihon and Og during their conquest of the land (Numbers 21:21-35). Joshua 12:4 describes king Og as “the last of the Rephaim.”

What marked the two kings as Rephaim? The biblical writers noted their height. Deuteronomy 3:8 calls them “kings of the Amorites” (a general term for inhabitants of Canaan), and Amos 2:9-10 reports how God beat each of the giant Amorite kings, “I destroyed the Amorite before them ... whose height was like the height of the cedars and whose strength was like the oaks.” These guys we’re big.

King Og actually had a 13-foot long bed according to Deuteronomy 3:11! However, the length of Og’s bed is not just an indication of his height. Michael Heiser in his ground-breaking book The Unseen Realm (p. 198) about the Nephilim, "Sons of God", Hermon, Rephaim and more notes that the exact dimensions of Og's bed (9 cubits by 4 cubits) “are precisely those of the cultic bed in the ziggurat called Entemenanki.” That bed in an ancient Babylonian mountain temple, called a ziggurat, is prepared for gods who come down from heaven to visit earth. It’s another connection between these Rephaim kings and the spiritual realm.

We can’t make total sense out of the mixture of legend and history, but the general point is clear. Mount Hermon, in the land of Bashan, was a place where the divine mixed with humanity. Evil spirits originated there. Great kings returned from the dead there. And that’s just the beginning of the legends surrounding Mount Hermon.

Ancient Canaanite literature calls Mount Hermon and other high mountains in Lebanon (such as Zaphon and Lalu) the meeting place of the gods. The council of ancient Canaanite gods assembled on top of these mountains. As a late Old Babylonian fragment of the Epic of Gilgamesh (ANET 504, 5:C:13) states, “the dwelling-place of the Anunnaki” (“Annunaki” is a group of gods) is in “the Lebanon ranges.” Mount Hermon’s sheer heights and its deep watery abyss made it a natural connection point for heaven, earth, and the underworld.

Judges 3:3 and 1 Chronicles 5:23 both mention “Baal Hermon”—a Canaanite deity who lived on Mount Hermon. Baal was the most powerful god among the gods in the region. He could gather the divine council there. As a result, Hermon contended with Zion to be the true “mountain of God.” But the kings of that mountain in the north, Mount Hermon, failed to win the fight, according to the Psalms.

Psalm 68 recounts the superiority contest between Mount Hermon and Mount Zion. Psalm 68:15–16 says:

A mountain of the gods (Elohim) is the mountain of Bashan

A mountain of many peaks is the mountain of Bashan.

Why do you look with envy, O mountains with many peaks,

At the mountain which God (Elohim) has desired for His residence?

Surely YHVH will dwell there forever.

This Psalm mocks the fake gods who live on the mountain of Bashan. It recounts how God led Israel to victory over King Og and Sihon in Bashan, but then chose to permanently make Mount Zion his home in the land. God conquered the region of Bashan but picked Zion for his permanent residence.

When Psalm 68 recounts how God wiped out the kings who stood in the way of his people, it describes a victory ceremony where Israel gets to stomp on its defeated enemies. It praises God as the one who chases down and captures all of Israel’s enemies wherever they try to hide. In Psalm 68:22 Yahweh says, “I will bring them back from Bashan. I will bring them back from the depths of the water.” Amos 9:1-3 tells a parallel story that talks about God pulling people back from mountain summits and the floor of the sea. Pulling people back from the heights of Bashan and the depths of the sea meant Yahweh was more powerful than all the other gods who were supposed to control those regions.

When Jesus and the disciples stood at the base of Mount Hermon to discuss Jesus’ true identity, they were standing in the territory of gods whom Yahweh had defeated. And Jesus was proclaiming that he would be victorious there too. But his specific battle would be against the “Gates of Hades.”

The “Gates of Hades” is a natural periphrasis for death itself. I know that is a big word, periphrasis, but let me explain. When Hezekiah speaks of his impending death in Isaiah 38:10, he uses a similar phrase: “I shall pass through the gates of the grave, I am deprived of the rest of my years.” Passing through the “Gates of the grave” means Hezekiah will die. The Wisdom of Solomon 16:13 uses the exact phrase from Jesu’ statement, “You have the power of life and death. You lead to the gates of hades and bring up again.” The Wisdom of Solomon was written in the 1st or 2nd Century BC after the Greeks had conquered the Jewish homeland and before Jesus came on the scene. It shows how the Jews had started to use Greek expressions. Going in and out of the “Gates of Hades” meant dying and rising again. So when Jesus speaks about the “Gates of Hades,” he is speaking about going in and out of death.

But Jesus wasn’t just speaking generically about death. He was standing in a region known for dying and rising kings next to a giant hole in the rock Hermon that people believed was the entrance to the realm of the dead.

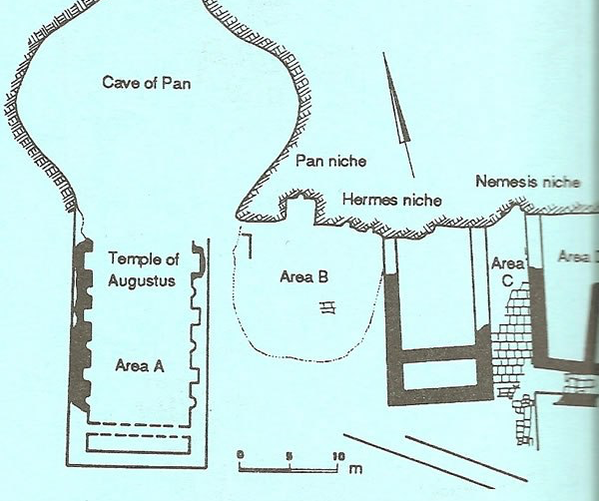

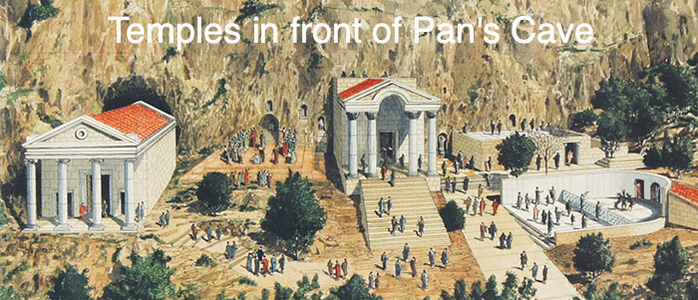

When the Greeks came to town during Alexander the Great’s conquest, they built shrines to Pan around the cave and its watery abyss. They sacrificed goats and threw the carcasses into the water to see if they would sink. When they sunk, it meant the gods of that realm were pleased.

According to a narrative at his temple, Pan was one of the few gods who could cross into Hades and return to earth. Why? Because he was the son of Hermes. Hermes was the god who guided souls of the dead to Hades. So his son Pan ran around near the thresholds of that realm with the freedom to enter.

Hermes himself is likely the inspiration for the mountain’s name. Deuteronomy 4:48 tells us the Hebrews first called the mountain, “Mount Sion.” And it goes on to explain that Mount Sion became known as Hermon.

The original name Sion finds parallels in Phoenician literature, where it is called Sirion. Deuteronomy 3:9 explains, “Hermon is called Sirion by the Sidonians; the Amorites call it Senir.” Why Sirion? In Greek legends, Hermes came to earth to teach the Egyptians about civilization and then returned to the stars. Specifically, he returned back to the main star in the constellation Canis Major, Sirius. This legend is likely the reason for calling the mountain Sion, Sirion, or Hermon. All the names recall Hermes and his ascent to the star Sirius. They show us how dominant the stories of Hermes and his son Pan influenced the area. The shrines to Pan and Hermes, carved into the rock face, demonstrate their influence.

So What Was Jesus Really Saying?

At the entrance to the dead, at a rock where gods assembled on the summit, and in a region known for powerful semi-divine kings who returned from the dead, Jesus‘ words reverberate with a whole new depth of meaning:

“You are Peter,

and on this rock I will build my church,

and the gates of Hades will not be able to stop it”

- Matthew 16:18

Many scholars have wrestled with the choice to link “the rock” on which Jesus will build his church to either Peter or the rock face at the foot of Mount Hermon. But it appears to be a double entendre. Both (1) Peter who confessed that Jesus is the king sent by God and (2) the rock cave whose watery abyss represents death itself are foundational to what Jesus is building. Jesus is going to use his resurrection from the dead and those who testify to it as the foundation of the church’s growth. As Ephesians 2:19-20 says, “the household of God [is] built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets.”

Peter, and all the other apostles after him who proclaimed that Jesus is the real King (“Messiah” = God’s anointed king), are the solid foundation on which the church was built. The foundation, or solid rock, is greater than the great rock, Hermon, that Jesus and his disciples are looking at in Caesarea-Philippi. Many other great kings had supposedly come from rock Hermon, and other divine councils had assembled at its peaks. But Jesus is the greatest king to assemble his team at the mountain. Remember, the Greek word for church, ekklesia, means assembly. So Jesus is countering the age-old stories about the significant assembly of gods that gathered "upon this rock." He has assembled his council on rock Hermon that will now redirect human history.

And what do we make of his claim that “the Gates of Hades will not be able to stop” what he is building? He is talking about death. The power of death will not be able to stop the growth of Jesus’ new community. In fact, Jesus’ death will become the foundation on which his movement will find its ultimate meaning.

In the scene immediately following Jesus’ words, he informs his disciples about his coming suffering, death, and resurrection (Matthew 16:21). It all seems to fit quite nicely now, but Peter didn’t like the idea. In his mind, Jesus couldn’t be killed. It would ruin the entire enterprise he had started. So Peter told Jesus he was wrong. “God forbid, Lord! This shall never happen to you” (Matthew 16:22).

Yikes! Peter had just gotten Jesus’ identity right in the preceding scene and now he is trying to tell Jesus that he is wrong about his coming death. Peter is certain about it, but he is certainly wrong. He is refusing to believe that Jesus himself will be pushed through “the Gates of Hades.” So Jesus has to fire back with a powerful and poignant rebuke in front of the entrance to evil’s lair, “Get behind me, Satan” (Matthew 16:23).

Yikes again! Peter has blown it. He has aligned his thinking with Satan’s original temptation in Jesus’ wilderness experience (Matthew 4:1-11). Satan had wanted Jesus to think he could set up his kingdom without ever suffering for it. But Jesus knew he had to suffer death, and he knew it still couldn’t stop what he was building. He would go right through the “Gates of Hades” and come back more powerful than before. The rest of King Hezekiah’s days might have been taken from him at death, but Jesus was different. Peter eventually saw it happen and then boldly proclaimed in Acts 2:24, “God raised him up again, ending the agony of death, because it was impossible for Jesus to be held down by its power.”

When Jesus predicts his death and return to life, you can hear the echoes of the old Canaanite legend about great warrior kings who return to earth after dying in battle. But Jesus isn’t coming back as a ghostly, evil spirit or gigantic king whose kingdom can be defeated again. He is going to break out of Hades’ Gates to build a church that won’t even die when his disciples do.

Two thousand years later, that church has grown to over two billion people around the world. And the blood of slaughtered saints has become the seed of the church. Death couldn’t hold Jesus down, and it couldn’t stop what he started.

All of us are going to die one day, but don’t worry. Death itself can’t stop what God is doing in the world. And in fact, your life and your death can further Jesus’ mission. So prepare yourselves with what Jesus told Peter and his disciples, “If anyone wishes to come after me, he must deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever wants to preserve his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life for my sake will find it.”

NOTE: To read a full scholarly discussion of the local legends about dead warrior-kings who returned to earth, see Michael Heiser’s research on the Rephaim

RSS Feed

RSS Feed