How did those Jews in Jerusalem break the covenant? That story started long before the time of Jesus. After the successful second-century BC revolt of the Maccabees and the reestablishment of an independent Jewish state, the Hasmonean kings (from the Maccabee family) eventually assumed not only the kingship but also control of the high priesthood. The king and high priest became one.

The Zadokites among the Essenes considered the non-Zadokite priests usurpers and declared their Temple sacrifices illegal. Although they could not function as priests in the Temple anymore, they followed the holiness standards for priests in ways deemed more authentic to the Torah. They separated themselves from the mainstream to form exclusive communities of the righteous. They studied the Prophets carefully and looked for God’s impending judgment of Jerusalem’s unfaithful leaders. They believed their community was the beginning of a renewed people of God in earth.

Jesus held many of the same beliefs. It has led some to theorize that Jesus himself should be called a Separatist, or even equated with the Teacher of Righteousness who led the Qumran community. But we have to look more closely at the Separatist communities to see where Jesus agreed and where he called for an even more radical way forward.

Philo reports that the separatist communities, whom he called Essenes, "are living together in large communities in several cities of Judea and in many villages” (Apologia pro Judaeis 1). Separating out to form a holy huddle had become standard practice for Jews who felt their religious leaders were suspect. These “Essenes” lived in isolated communities sharing all their resources with each other and isolating themselves from all outsiders. These communities formed not just at Qumran, near the caves where the Dead Sea Scrolls were found, but in many Jewish cities and villages, even in Jerusalem.

The Dead Sea scrolls themselves talk about more than one commune and a particularly special one in Jerusalem. The famous War Scroll (1QM), which describes an apocalyptic battle between the forces of light and the forces of darkness, refers to the sounding of trumpets when the victorious forces of light "return from battle against the enemy and they journey to the congregation (or community [ha-edah]) in Jerusalem” (1QM 3.10-11). Josephus also mentions a certain Essene teacher named Judas living in Jerusalem in 104 BC (Ant 13.311). Later, Josephus reports, the youthful Herod the Great met an Essene named Menahem (Ant15.373). They could be found in the city, even though many of them separated their living quarters from mainstream society.

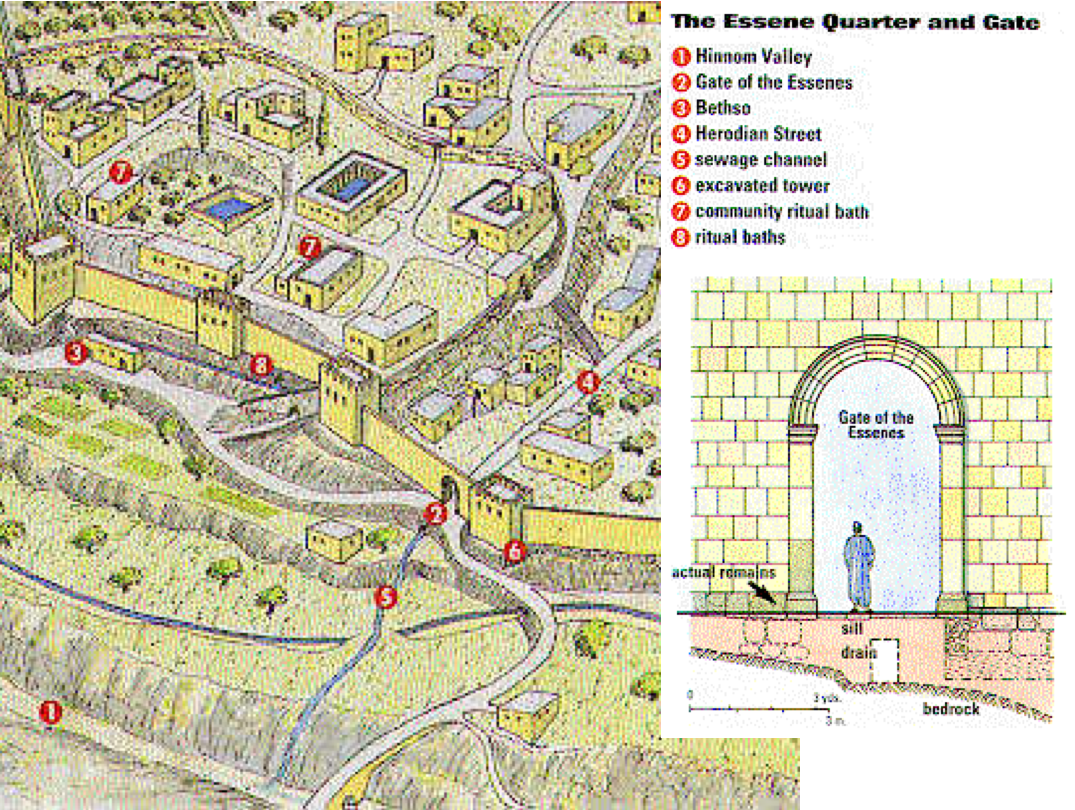

Where did the Separatists live in Jerusalem? Archaeological remains have identified an “Essence Quarter” in the southwestern corner of Jerusalem with its own gate in and out of the city.

Archaeological remains indicate about 50 Essene kohanim (priests) may have lived in the southwestern corner of Jerusalem between 30 BC and 70 AD. Mostly celibate, the kohanim adhered to purity laws far stricter than those followed by Jerusalem Temple priests. To maintain such purity, the priests needed to bathe frequently and exit the city to do impure activities (i.e., take a dump).

The Gate of the Essenes, which was cut into a pre-existing city wall, gave the priestly community access to their ritual baths, or miqva'ot, and latrines outside the city wall. A double miqveh was found about 160 feet outside the Essene gate. The location and purpose of the structures match the description in the Temple Scroll (11Q19) found at Qumran.

| The location of the miqva'ot outside the Wallis is significant. Deuteronomy 23:11-12 states that when someone contracts impurity because of a nocturnal emission (remember that many of the Essenes were celibate), "he must go outside the camp; he must not come within the camp. When evening comes, he must wash himself with water. When the sun has set, he may come back into the camp." The Essenes regarded the entire city of Jerusalem as equivalent to the camp. As the Temple Scroll states, "Jerusalem is the camp of holiness." One of the two miqva'ot had a divider between the steps of descent and the steps of ascent, the same as miqva'ot, found at Qumran. The steps of ascent allowed the purified bather to exit without recontamination. They didn’t want to touch the contaminated water that cleansed them on the way in. They took ritual purity to a whole other level. |

Historians have investigated the relationship between Essene communities and early Christian leaders. Due to some similarities, a few unregulated voices online have posited that Jesus was an Essene, but noted Qumran Scholar James VanderKam paints a more historically accurate picture in his conclusion: “The Qumranites and the early Christians, both of whom considered themselves members of a New Covenant (2 Cor 3:6; CD 20:2), were children of a common parent tradition in Judaism.”

Both groups viewed themselves as the keeper of the New Covenant promised in Jeremiah 31:31. They each believed their communities were the founding members of a new kingdom God was establishing on earth. To speak to their select group of followers, both Essenes and Jesus used similar symbolic language. Just like Jesus’ parables were designed to teach his disciples and confound outsiders, the Damascus Rule at Qumran describes the same strategy for their teacher: “He shall conceal the teaching of the law from deceitful men, but shall impart a knowledge of truth and righteous judgement to those who have chosen the way.”

Christians and the Qumran commentaries on the Prophets both expected an imminent judgment on the corrupt leadership in Jerusalem. And to be part of their new righteous communities, initiates in both movements were baptized and expected to hold all property in common. These shared beliefs and practices are why studying the Dead Sea Scrolls have taught us so much about the contours of New Testament teaching and practice.

These similarities are equally matched by their differences. The Essenes rejected the Temple sacrifices but maintained an alternative priesthood who offered separate sacrifices. Jesus’ people ended involvement with all sacrifices. The community at Qumran held to strict religious observances on holy days determined by a solar calendar, while Jesus freed his followers from attaching holiness to ritual. Essene priests and Qumran community members bathed daily to stay pure while Jesus said purity of the heart is what matters, not just a clean body (Matthew 23:25-28). The Qumran Community Rule told initiates to hate their enemies while Jesus challenges his followers to love their enemies. These differences show us that although Jesus diagnosed the problem with Israel’s religious leadership much the same way that the Essenes did, he had a much more radical solution.

The Essene community that separated itself from everyone else had biblical justification. They explained their Separatist movement through the words of Isaiah that direct God’s Servant to go out into the wilderness. As the Community Rule states, “They shall be separated from the midst of the gatherings of sinful men to go to the wilderness to prepare there the way of the Lord, as it is written: In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord; make straight in the desert a high way for God.” The Essenes believed separation was essential to distinguish themselves as a holy people living faithfully by their covenant with God.

Unfortunately, the separatist community at Qumran misunderstood a metaphorical reference to building roads in the desert as a concrete command to actually go live in the desert. We often make the same mistakes interpreting biblical language. But in the Ancient Near East, local populations were expected to pave roads (see Walton’s Bible Background Commentary on Isaiah 40:3). Isaiah was telling people to do what they needed to do to prepare for God’s return to Jerusalem, not to leave Jerusalem. Isaiah envisioned God’s presence among God’s people, not God’s people vacating the very cities that needed them most.

Jesus agreed with the Essene assessment of Temple corruption, but he didn’t agree with their solution. Taking light out of the darkness didn’t help anyone wandering around in the dark. Jesus told his followers in the Sermon on the Mount, “Don’t hide your light!” Or as Matthew 5:16 states, “Let your light shine before men in such a way that they may see your good works and glorify your Father who is in heaven.” But that’s not what these Separatist communities decided to do. The Essene “sons of light” boxed up what they had in holy huddles and left the rest of their compatriots in darkness.

Jesus’ love knows no bounds. He kept going to Jerusalem to rescue anyone he could, even knowing Jerusalem’s judgment was coming. He didn’t hide his voice in the wilderness. Rather, he cried out everywhere he could. That’s why his closest disciples included a priest (John) and a tax collector (Matthew), a revolutionary Zealot (Simon) and fishermen (Peter and Andrew).

Jesus didn’t make his followers jump through ritual hoops. He focused on a transformation of the heart. He taught us to love our enemies, not to hate them and exclude them. His radical, unhiding, unrelenting love led to his demise, but it also led to the redemption of many. He wasn’t satisfied to be on the right side; he wanted to persuade as many as he could to follow him.

Retreat and seclusion are easy. But Jesus didn’t show us an easy way to follow. That’s why we must enter every segment of society to give every person a shot at redemption. If someone entices you to withdraw into a holy huddle, that one is not following Jesus’ path. They are carving out their own little kingdom with barriers too big to embrace a world in need.

When Jesus compared his kingdom to a king’s wedding feast, his true servants “went out into the streets and gathered together all they found, both evil and good; and the wedding hall was filled with [e]dinner guests” (Matthew 22:10). Let’s make sure everyone gets a shot at redemption.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed