Everything leading up to Mark 8:29 is designed to reveal who Jesus is, but everything afterwards redefines what the disciples think about the Messiah. Jesus immediately begins to correct their assumptions about what the Messiah will do. “And He began to teach them that the Son of Man must suffer many things and be rejected by the elders and the chief priests and the scribes, and be killed, and after three days rise again” (Mark 8:31). Jesus had to teach them about his torturous destiny over and over again (Mark 9:12, 31-32; 10:33-34). Why? Because the disciples already thought the Messiah would kill all the bad guys, not get killed by them.

When Jesus told the disciples that the Jewish oligarchy would kill him, Peter took him aside and rebuked Jesus (Mark 8:32). Peter didn’t think Jesus knew what he was talking about. If Jesus was the Messiah, his destiny wasn’t death but autocracy. God was going to give him victory over foreign nations and sinful insiders so that he could reign supreme over an independent Jewish nation on earth. That’s why John and James ask for the privileged positions of sitting at the right and left sides of his throne when God crowns Jesus the king (Mark 10:35-37).

The disciples had expectations for the Messiah because Jews had been talking about it for years. They had blended God’s prophetic promises with nationalistic ambition. They were already so certain about the Messiah’s unstoppable political establishment that they were ready to rebuke Jesus for thinking otherwise. That belief was rooted in powerful Jewish voices that have been preserved to this day in Greek translations of ancient Hebrew texts.

One of the clearest portraits of the Messiah in Jewish Literature dating to the century before Jesus’ life is in the Psalms of Solomon. Likely written in the latter half of the first Century BCE after Jewish oligarchs struck a subservient deal with Rome, the 17th Psalm envisions a new Jewish king in the line of David. The Psalms of Solomon encapsulate a dominant voice in Jewish conversations that extended into Jesus day in 1st Century AD Israel—echoed in rabbinic and Qumran teachings. If you have not read them, you won’t know why Jesus has to repeatedly correct the disciples’ mistaken destiny for the Messiah.

In Psalm of Solomon 17, the Messiah is depicted as a righteous conqueror, who marries religious purity with political supremacy (ever see Christians make that same mistake today?):

23 Behold, O Lord, and raise up for them their king, the son of David, at the time in which you see, O God, that he may reign over Israel Thy servant 24 And gird him with strength, that he may shatter unrighteous rulers, 25 And that he may purge Jerusalem from nations that trample (her) down to destruction. Wisely, righteously 26 he shall thrust out sinners from (the) inheritance, he shall destroy the pride of the sinner as a potter's vessel. With a rod of iron he shall break in pieces all their substance, 27 He shall destroy the godless nations with the word of his mouth and at his rebuke nations shall flee before him, And he shall reprove sinners for the thoughts of their heart.

Messiah Will Never Be an Earthly Political Autocrat

Jesus disagreed. When Peter tried to give him the Psalm of Solomon 17 version of Messiah, Jesus responded: “Get behind Me, Satan; for you don’t care about God’s interests, but about human desires” (Mark 8:33). The political autocrat is what people might want, but Jesus said God was not really interested in that kind of king over a kingdom in Jerusalem. That’s a radical counterpoint in an old Jewish conversation.

So what kind of Messiah would Jesus be? Jesus taught by word and deed in Mark 8-16 that the Messiah and his followers suffer on a journey to establish a heavenly kingdom. Suffering with integrity to expose injustice on earth (rather than political dominance through compromise of character) was the path of Messiah. That path exulted a new ethic—a nonviolent plan to redeem the world. Shaming injustice by exaggerating its errors through the unjustified suffering of the righteous becomes the new way subjects will serve their king who suffered. Inspiration from example rather than coercion by force is Jesus’ plan to change the world.

Jesus finds the entire pursuit of political power corrupt on all sides. He introduces an ethic that goes beyond self-serving prophetic portraits of successful power-grabbing. He contradicts the most popular political theology in Jewish circles and focuses on a king exalted in heaven who was willing to die on earth to protest sin and injustice. To be quite honest, Jesus did not fulfill the messianic hopes of his Jewish contemporaries but rather dashed their messianic dreams by redefining the path and purpose of the Messiah. We miss this point, and we can miss what Jesus was all about if we’re deaf to the dominant voices he was debating in his day.

Jesus did not start from scratch. He did not pick out his disciples and begin whiteboarding the way to “heaven on earth.” He had no tabula rasa on which to write his commands.

Jesus entered into a live conversation. The words he used had already been defined by the discussions people had before he appeared. As soon as Jesus said who he was, he had to redefine everyone’s assumptions.

If we do not hear the other voices in the conversation, we will not understand what Jesus taught. Jesus was not just making points. He was making counterpoints. His teachings were not just heavenly conjecture from the Son of God; they were targeted corrections to what other people taught on earth.

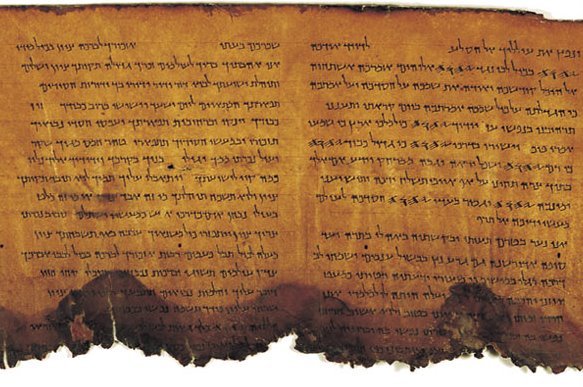

His good news of “rest from a burdensome yoke” in Matthew 11:28 must be heard in a rabbinic debate. The angels in Luke 2 proclaiming Jesus’ birth is good news of great joy that will bring peace on earth challenge a Roman imperial claim about the peace established by Caesar Augustus. The Sermon on the Mount redefines God’s law when you read it among the voices of the Dead Sea Scrolls predicting the next great revision to Deuteronomy. Heaven and earth passing away must be read alongside Josephus and rabbinic commentaries so we hear him predicting the Temple’s destruction and not the end of the world. The context of the conversation controls the meaning of words and the content of Jesus’ message.

If Jesus’ words are heard in our western assumptions rather than rooted in Ancient Near Eastern debates, then we will miss his meaning and make up a westernized message. And Jesus’ message is too important to distort with our modern ideas and ambitions.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed