‘Are You the King of the Jews?’ — John 18:33

The tension had been tightening ever since Pompey the Great’s siege of Jerusalem in 63 BCE. That Roman siege ended the independence of Judea, and people immediately began dreaming of the day God would free them from Roman oppression. In 6 AD, the Roman governor of Syria, Publius Sulpicius Quirinius, turned those dreams into a deadly struggle.

Quirinius inherited responsibility to rule over Judea when Herod’s son Archelaus was deposed. His rule over Judea switched their status from a client kingdom of Rome to another province in the Empire. That change in political status incited a revolution.

Quirinius’s first act was to count his new constituents to know how much taxes he could collect. Luke 2:1-5 mentions the “census” of Quirinius and its goal of taxation. That decision mobilized a group of theocratic nationalists who believed God alone was the ruler of Israel and paying taxes to Rome was an act of mutiny.

Judas of Gamala led the movement, called “kana’im” in Hebrew (קנאים), which translates in English to “zealots.” He incited his countrymen to rebel against Rome. Their first act was to attack Sepphoris, a city in Galilee. He needed weapons and money to arm his band of revolutionaries. Josephus describes it in his book, Jewish Antiquities:

Judas was the son of that Hezekiah who had been head of the robbers. (This Hezekiah had been a very strong man, and had with great difficulty been caught by Herod.) Judas rallied a bunch of rough characters and assaulted the palace of Sepphoris in Galilee. He took all the weapons stored there and armed his men and stole the money found there. He treated everyone terribly, tearing and shredding those that came near him in order to exalt himself. He had the ambitious desire and goal to become king, not because of his virtuous skill in war, but because of his extravagant violence. (Flavius Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 17.271-272)

The revolutionaries didn’t disappear after Judas’ death. Judas' sons James and Simon (who may have been sons of his revolutionary sentiment rather than biological offspring as Josephus claims) led another rebellion that the Roman procurator Tiberius Julius Alexander squashed around 46 CE (Josephus, Ant.20, 100-103). The last great rebellion against Rome before Jerusalem’s Temple was destroyed in 70AD was led by Menahem ben Judah, whom Josephus similarly counts as Judas' "son." His cousin, Eleazar ben Ya'ir, led the final stand against Rome at the fortress of Masada.

What Judas of Gamala started in 6 AD was only one attempt in a series of Jewish revolts against Rome. Gamaliel counted them all among failed Messianic movements alongside other messianic figures like Theudas and “the Egyptian.” He reasoned before the Sanhedrin in Acts 5 that the movement emerging in the name of Jesus the Nazerene could similarly fail. The comparison implied Jesus’ followers were all part of another revolutionary movement that likely wanted to overthrow Roman rule. This revolutionary context is why many historians have hypothesized that Jesus himself was just another violent revolutionary whose followers changed his message after his death.

The connection between Jesus and other revolutionary movements in the first Century AD made Jesus a target of Roman suspicion when he was alive. It gave Pilate good reason to ask if Jesus was one more revolutionary leader hoping to attack the Romans and declare himself king.

But Jesus didn’t fit the mold. He did claim to be God’s anointed one, the Messiah (see Mark 14:61-62). The Messiah had been equated with the king of a nation-state by Jesus’ Jewish contemporaries. So Jews would expect that king to act just like other kings—to take and hold power through politics and violence. But Jesus wanted nothing to do with that.

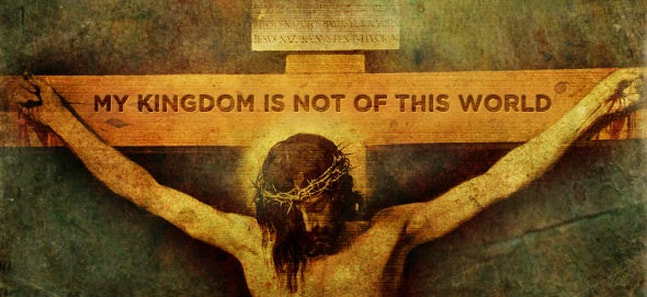

When Jesus was brought before Pilate to determine his fate, he redefined what kind of king he was by redefining what kind of kingdom he ruled. Pilate followed up his question, “Are you the King of the Jews?,” with the question: “Your own people and chief priests handed you over to me. What is it you have done?” Jesus explained,

“My kingdom is not of this world. If My kingdom were of this world, then My servants would be fighting so that I would not be handed over to the Jews; but as it is, My kingdom is not of this realm.” - John 18:36

The Jewish assumption that God’s anointed ruler was no different than nationalistic kings goes all the way back to king Saul. The Hebrew Bible recalls a time when Israel had no king—when God’s people only needed prophets who proclaimed God’s passion and purpose for them. But the tribes of Israel struggling to establish themselves among the nations were not content with being an alternative community marked by character rather than power, by justice rather than domination, by mercy rather than oppression. So they asked for a king like all the nations.

When you place Jesus in this context, he didn’t just buck the 1st Century trend of political Messiahs threatening Roman rule; he actually corrected a centuries-old mistake dating back to King Saul.

“Now appoint a king for us to judge us like all the nations” (1 Samuel 8:5). That’s what Israelites wanted around 1000 BC. Samuel didn’t want to do it. But he took it to God. And God said, “Listen to the voice of the people in regard to all that they say to you, for they have not rejected you, but they have rejected Me from being king over them” (1 Samuel 8:7).

God’s response reveals Samuel’s heart. He had taken their request as an insult. He heard their request as a personal rejection. But God made it clear. You didn’t fail. They have failed. They have failed to be satisfied with God. Getting his word for how to live was not good enough.

The tribes of Israel did not want to transcend the world around them. They wanted to structure their community like other countries. They didn’t want to just be a light to the nations. They wanted to be a powerful nation. They wanted a king who killed their enemies and wielded power in the political realm.

God told Samuel to “warn them” about what kings do. So he explained to Israel how kings that you think will serve your interests actually end up making you serve them. But Israel didn’t care. They ignored his warning and said, “No, there shall be a king over us so we can be like all the nations” (1 Samuel 8:19).

1 Samuel 8 repeats the phrase “like all the nations” to emphasize the error at the heart of Israel’s request. They didn’t want to be different. They said: we want a powerful king to “judge us and lead us and fight our battles” (1 Samuel 8:20). That misguided demand would warp everything God wanted on earth until Jesus came. The rest of the Old Testament, the rest of Israel’s story, took a deadly turn from that point forward. God’s dream for “a kingdom of priests, a holy nation” (Exodus 19:6) was dashed. A people that God wanted to be separate from the world (i.e., holy) had chosen to be just “like all the nations.”

Why is that such a big problem? Because you can’t have a king and kill your enemies and be different. You can’t create hierarchy and control others through coercion and show God’s love. The structure of political power undermines even the best of intentions to be a beacon of hope. What Western history books call the “Holy Roman Empire” is an oxymoron. I’m sorry Christian America, but it doesn’t work. You can’t stand out in the world as a community whose way is rooted in God’s words when you look and act “like all the nations.” Jesus knew that. It’s why he told Pontius Pilate, “My kingdom is not of this world. If My kingdom were of this world, then My servants would be fighting” to preserve it.

If you followed the investigation of Russian meddling in the 2016 Election in the USA, you have read about Maria Butina. She was indicted as a Russian spy. What was her crime? She tried to arrange meetings between Russian and American politicians. What venue did she choose to arrange some of those meetings? The National Prayer Breakfast.

At first, it sounds like she was using an a-political event for clandestine purposes. But the original purpose of the National Prayer Breakfast was very political. The founder, Abraham Vereide, was not happy with how slow his strategy for changing society was working. Despite launching a hugely successful ministry in Washington state, Goodwill Industries, he moved to Washington D.C. to influence “key men” who could shape national and international policy. His efforts to establish a National Prayer Breakfast under FDR and Truman failed, but Billy Graham helped convince Eisenhower to attend in 1953. Now 3,000 to 4,000 national and international leaders attend every February.

Abraham Vereide’s vision was to influence, and even put in office, politicians who would legislate Jesus’ teaching. Jeffrey Sharlet, who has researched and written two books on the Foundation behind the event (internally called “the Family”), describes Vereide’s strategy:

[Vereide] felt that God spoke to him and told him that Christianity may have been getting it wrong for 2,000 years, with this focus on the poor and the weak and the down and out, and what God actually wanted was for Abraham — and those whom he chose — to minister to those whom he called the “up and out,” the “key men.” He had this idea that if you could win a few key figures in positions of power for their idea of Christ, well, then they would reorganize society on that basis. – Burton, Vox

An Alternative Community

Peter called Jesus’ followers “aliens and strangers” in the world. “Aliens and strangers” is a poor English translation for foreigners without citizenship. It reflects Jesus’ a-political approach to changing the world. Peter told us that Jesus’ plan is for the world to “see the way you live and glorify God because of what they observe” (1 Peter 2:11-12). That approach shouldn’t threaten, or even necessitate the involvement of, politicians. That’s what Jesus tried to explain to Pilate when the Prefect of Rome inquired about Jesus’ political ambitions.

Jesus wants us to influence the world. He taught us to pray, “May your Kingdom come, may your will be done on earth as in heaven.” But he didn’t teach us to enforce the kingdom on earth. We are a community that defies any national allegiance because our king is not nationalistic. We are an alternative community that subversively influences the world through our example. We can’t vote Jesus’ kingdom to come. We don’t make his will be done on earth through political revolutions. We must exercise patience and live profoundly. That’s what our king requires of those of us who give allegiance to him.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed