However, the overlap between First-Century Jewish culture and Jesus’ Way has limits. Jesus not only embodied his culture and embraced its accoutrements; he also challenged its everyday assumptions.

"Seat of Moses" in Chorazin Synagogue

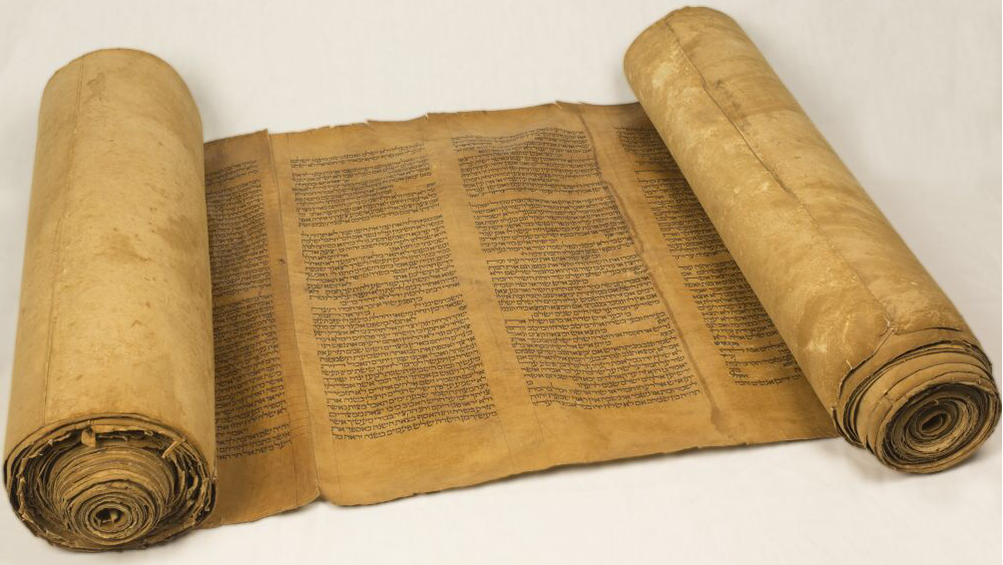

"Seat of Moses" in Chorazin Synagogue In First-Century Israel, God’s people were easy to find. Just go to a Synagogue on Saturday. God’s people showed up there to figure out what God wanted. And specially trained men told them what God thought.

Most synagogues had a special seat for authoritative Rabbis, the “Seat of Moses.” The most highly revered teachers had s’michah (Hebrew סמיכה). What is that? S’michah is the authority to tell someone what God required of them. The “scribes” or “teachers of the law” or “lawyers” mentioned in the Gospels only interpreted Scripture based on preceding opinions of authoritative teachers. Only a few Rabbis with s’michah introduced brand new interpretations of old Scriptural passages.

A Rabbi with s’michah had the power to decide what God permits (Hebrew sere/sera) and does not permit (Hebrew asar). Generally rabbis with s’michah received it through ordination from an established Rabbi with s’michah. These authoritative teachers with s’michah interpreted ancient Laws and Prophecies in new ways so that people knew how to please God in the present. That inside scoop made Synagogue attendance on the Sabbath essential.

Jesus threw a wrench into the Jewish hierarchy of authoritative teachers. He commandeered the Synagogue system and set up new authorities. In Matthew’s Gospel, we see 5 repeated references to “their synagogues” (Matt 4:23; 9:35; 10:17; 12:9; 13:54). The phrase “their synagogue(s)” draws a line of distinction between Jesus’ movement and the contemporary Synagogue system. Although Jesus spent many Saturdays teaching in Galilean synagogues, he eventually detached his movement from the Synagogue complex and created a new community.

Jesus uses the term ecclesia (assembly or church) to describe his new community in Matthew 16:18 and 18:17. It is the only use of the term in all four Gospels. It is designed to contrast “their synagogues” as Jesus sets up a counter-synagogue community.

However, the mere use of the term is not as significant as the way Jesus reassigns authority to his disciples. In both Matthew 16:19 and 18:18, Jesus shifts the power to “bind” and “loose” away from the Synagogues and its Rabbis. Matthew 16:19 gives that authority specifically to Peter, and Matthew 18:18 expands that authority to all his disciples using the second person plural.

“ Truly I say to you, whatever you (all) bind on earth shall have been bound in heaven; and whatever you (all) loose on earth shall have been loosed in heaven.”

Jesus did not just stop at giving his disciples the authority to apply Scripture in line with his hermeneutic. He changed the focal point itself.

“Again I say to you, that if two of you agree on earth about anything that they may ask, it shall be done for them by My Father who is in heaven. For where two or three have gathered together in My name, I am there in their midst.” – Matthew 18:19-20

You cannot understand his words or how controversial Jesus’ words are if you have not heard what other Rabbis were saying on the streets of First-Century Israel. Jesus is redrawing an old rabbinic paradigm:

“If two sit together and words of the Law (are) between them, the Divine Presence rests between them” – Mishnah Aboth 3:2

Instead of Jewish men gathering to determine how their lives should be ordered by the Torah, Jesus approves small groups who gather “in his name.” Gathering “in his name” means Jesus’ teaching and practice become the guide for how to understand God and obey Him. Gathering “in His name” means you intend to follow "in His way." His words become your commands. His character becomes your canon. Jesus becomes what the Torah has been. Now two or three people who desire to follow in his footsteps and live according to his character and teaching have God’s approval and presence. That is a radically new privilege that comes with weighty responsibility.

The followers of Jesus are now responsible to discern and declare the new way of being God’s people, what that is and sometimes what it is not. People gathered “in his name” discern what he prohibits (i.e., what has been bound in heaven) or permits (i.e., what has been loosed in heaven). They judge when someone has stepped outside the Way of Jesus.

Making those legal judgments were the exclusive territory of Rabbis in Jesus’ day. Those legal traditions were called Halakha. Davies and Allison are right to recognize that Jesus’ words transfer authority from select rabbis teaching Halakha to entire gatherings of Jesus’ disciples, “the halakhic decisions of the community [now] have the authority of heaven itself” (Davies and Allison, 787). That is a big responsibility to bear. And we better follow Jesus' promise not to burden people with excessive opinions. For he told us in Matthew 11:28-30 that his Halakha brings rest to the soul not a burden like other Rabbis with endless rules and restrictions.

The Power to Forgive or Declare Forgiveness?

In John 20:23, Jesus’ transfer of power to his disciples goes one step further.

“If you forgive the sins of any, their sins have been forgiven them; if you retain the sins of any, they have been retained.”

“If you perform your deeds well in this world, it shall be loosed and forgiven you in the world to come. But if you do not perform your deeds well in this world, your sin shall be retained for the day of judgement.”

Beth Din

Beth Din But Jesus handed heaven’s authority to his disciples. He supplanted the Jewish court system and gave his “church” (Matthew 18:17) the right to confront sin. They could decide when someone has been forgiven (John 20:23) or when someone must be excommunicated (Matthew 18:17). That is a frighteningly profound mantle to carry. That mantle requires the same sobriety demanded of judges in the Beth din who could not quickly issue a decision before understanding all facts related to the case and must display humility and reverence without arrogance or disrespect toward even the most ignorant in the community (see M. Sanhedrin 20).

The Verbs Matter

How can Jesus expect his assembly (“church”) of disciples to decide what God permits and prohibits, whose sins are forgiven or require excommunication? The verb tenses and voices in John 20:23, Matthew 16:19, and Matthew 18:18 give us helpful direction.

The verb tenses indicate that a disciple’s job is to discern what the heavenly court has decided first. The “perfect” tense and “passive” voice indicate that some other party has already determined what the disciples must decide. The “passive” voice of the verbs is a “Divine passive” that communicates God is the one who already did it. That’s an easy and obvious insight. But the “perfect” tense is harder to make sense of. If assembled disciples decide someone’s sins are forgiven (as Jesus tells them to do in John 20:23), why would Jesus say those sins had already been forgiven in the past (which is what the perfect tense communicates—a past action with ongoing effects)? The time sequence does not make sense to our chronological minds. What is Jesus really communicating?

Just like First-Century Jewish people believed the Sanhedrin judged cases on the basis of God’s Law and therefore accurately represented his will, Jesus wants his people to discern God’s will together. Disciples are tasked with the sacred job to discern God’s heart by following Jesus’ lead. Their goal is to proclaim what God has already pioneered. The grammar in all three passages (Matt 16:19; 18:18; John 20:23) shows that the community of Jesus’ followers does not determine who is forgiven or who has sinned. God decides, and disciples declare. His followers have been given the role to declare who stands right before God and who does not because of their knowledge of Jesus, his teaching and His Spirit. That is a solemn task demanding humility, training, and reverence.

When done right, Jesus’ people declare what God requires. They declare what God has reconciled. If that sounds too bold or too risky, I get it. Jesus’ plan seems dangerous—too much responsibility has been placed among too feeble a family of followers. We know the Sanhedrin system became corrupt and self-serving, but neither you nor I get to change what Jesus said.

When we do it well, just think how beautiful and life-giving it has been. High-church priests affirm absolution, and charismatic evangelists promise forgiveness to new converts. Rich Mullins decries materialistic Christianity, and Southern Baptist Russell Moore calls the President’s sin “sin” even when it nearly cost him his job. They are all doing their best to bear the responsibility of representing God to a world that does not know how ancient Scriptures still direct our faith and our footsteps in Jesus’ name.

Let’s be honest about the risks. Jesus’ non-hierarchical plan for discerning what God permits or prohibits, who he forgives or judges, is destined to create tension. One group of disciples will disagree with another assembly about God’s view on a matter. Just look at what’s happening with the Nashville Statement.

But it is a solemn and significant responsibility disciples must handle with care. It cannot be done alone. You don’t get to become an independent authority on God. Jesus uses plural verbs in Matthew and John. He promises his help when 2 or 3 assemble to discern what lines up with his Way. Therefore, we must both (1) obsess ourselves with grasping God’s character and (2) discern in community. We must know the nuances of Jesus’ life and teaching and bring them to bear on each situation in dialogue with other disciples. We must be deeply faithful to God’s priorities while creatively charting out what faithfulness looks like in a new land.

Jesus was a religious revolutionary. He relativized the Torah and its institutions like the Synagogue. He created a new Torah with his words, and a new community--the ecclesia, or assembly of his disciples. That undermined the pre-existing power structure built around God. It opened up a risky, wisdom-required, group dynamic where God’s people must gather “in his name” to discern what he’s all about. We must become deeply acquainted with the purpose behind Jesus’ every move so we can understand the character behind his every intention if we are going to discern his direction for today.

When we head down that path with other people who stay on that course, we can bear the responsibility to declare what God prohibits and what he promotes. We can announce his forgiveness to those who are uncertain of their status before Him. We can with authority free people from their fear of the false picture of Divine expectation they have been given by uninformed Scribes who couldn’t conceive how radical Jesus’ redirection really was. To do so, we must continue the path Jesus pioneered of faithfully representing God to the world. Jesus’ words in John 20:21 are the pattern, “As the Father has sent me so I send you.” So let us dissect Jesus’ counter-cultural, values-subverting, self-sacrificing, second-chance-creating example so we can be God-honoring disciples with s’michah.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed